Art Historian John Richardson, RIP at 95

Art Historian John Richardson, Who Wrote the Definitive Four-Volume Biography on Picasso, Has Died at 95

The author’s fourth and final volume on Picasso is due out this year.

British art historian John Richardson, known for his multi-volume biography of Pablo Picasso, died today at age 95. A representative from Knopf, Richardson’s publisher, confirmed the news.

The author’s long-anticipated fourth volume of A Life of Picasso is complete and scheduled to be published later this year, according to the Art Newspaper. “A publication date for the final volume has not been set,” the Knopf spokesperson told artnet News. “We will assess it all after the dust settles.”

Richardson was born in London in 1924. He studied at the Slade School of Fine Art and briefly went on to do window design for Harrods, as well as some textile designing. When it became clear that making art wasn’t in the cards for his career, Richardson turned to art criticism, writing for the New Statesman, the left-leaning British newspaper.

He then met art historian Douglas Cooper, who would become Richardson’s partner for ten years. They moved to Provence in the south of France, where Cooper introduced Richardson to Picasso in 1948. A close friendship developed between the two men.

Picasso “was very generous to me. He sensed somehow that I was going to write about him. He had a very strange understanding of his work,” Richardson told journalist Alain Elkann in 2016. “When I decided to write about him, originally it was going to be about a specific part of his life, his portraiture, about the people he met, going back to the early years.”

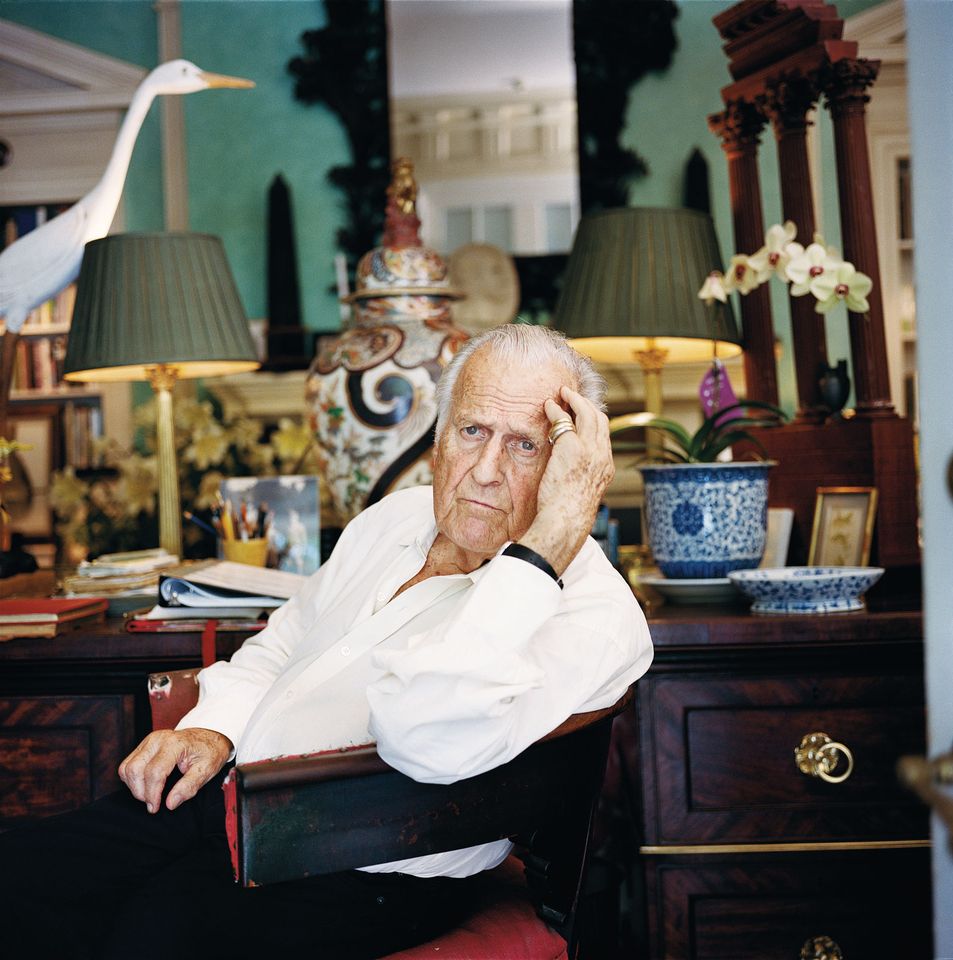

John Richardson’s home with a portrait of him by Andy Warhol. Photo by François Halard, courtesy of Rizzoli.

Richardson was also a close friend of Andy Warhol. He appeared in one of the Pop artist’s films and gave the eulogy at his memorial. Queen Elizabeth II knighted Richardson in 2012. (Her great-grandfather, King Edward VII, previously bestowed the same honor on his father, Wodehouse Richardson.)

In the 1960s, Richardson opened the New York office of Christie’s auction house and ran it for nine years before joining New York’s Knoedler & Co. gallery. The biography on Picasso became Richardson’s primary focus in 1980.

The first volume, The Prodigy, 1881–1906, was published in 1991 and was named the Whitbread Book of the Year. The Cubist Rebel, 1907–1916 followed five years later and the third volume, The Triumphant Years, 1917–1932, appeared in 2007.

“As I get older and older, I get more and more astonished the deeper I get into his work,” Richardson told ARTnews in 2012. (At the time, he was aiming for a 2014 publication date.) Some reports have suggested that the final volume will cover the rest of Picasso’s life, but in 2016, Richardson told Elkann that he was considering concluding either in 1940 or at the end of World War II, in 1944. (Picasso died in 1973.)

This month Rizzoli is publishing John Richardson: At Home, a book showcasing his various residences around the world, their “Bohemian Aristocrat” interiors, and his personal possessions, which include photographs, correspondence, and art from Picasso himself.

“He would sometimes embellish the letters his wife Jacqueline wrote to me or Douglas [Cooper] with little vignettes,” writes Richardson in the book.

Richardson was also in the process of curating an exhibition of Warhol’s celebrated society portraits for Gagosian Gallery in London, which is expected to open this year.

“In every conversation with John, he taught you something new—he could reveal things about a painting and its history that no one else could know. It was magical,” said Larry Gagosian in an email to artnet News. “The depth of his knowledge was astounding. It’s not just the passing of a friend, but the passing of an era. We won’t see another like him.”

See Works From Picasso’s Tender Early Years as They Take Center Stage at the Fondation Beyeler

The artist’s Blue and Rose periods are the focus of the exhibition in Basel, Switzerland.

At this point in history, the oeuvre and legacy of Pablo Picassohas been presented from almost every possible angle. But a new show at the Swiss museum Fondation Beyeler manages to show a side of the artist we don’t often see: his tender early years.

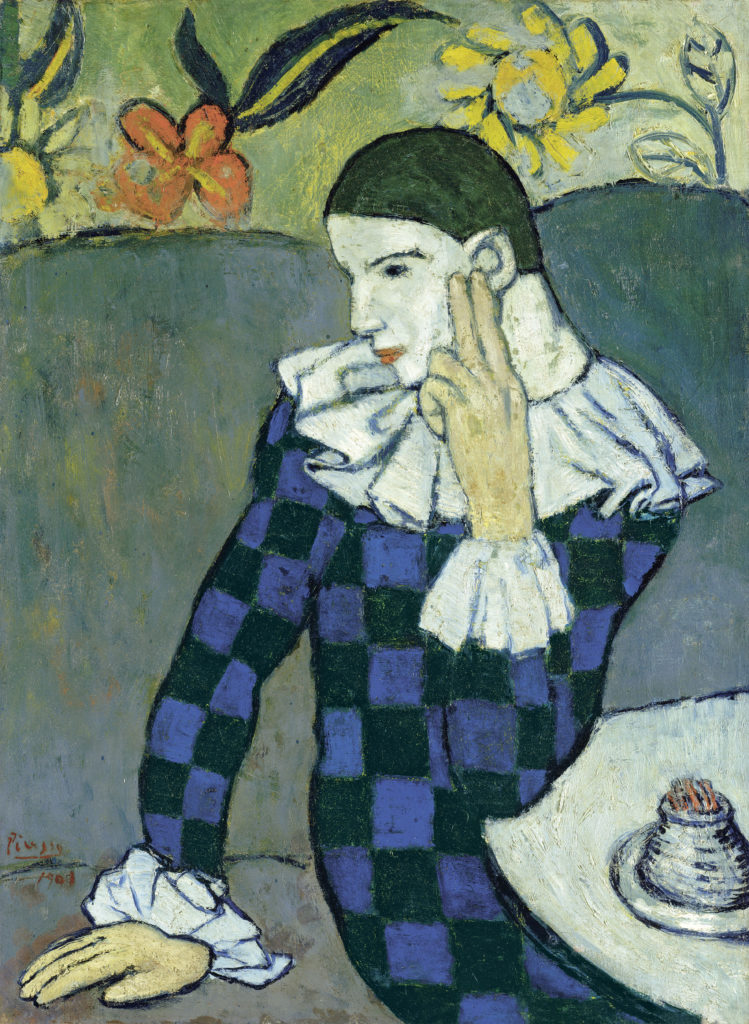

On view at the Basel institution until May 26, “The Young Picasso: Blue and Rose Periods” looks at the Spanish painter and sculptor during the tender time of his early twenties. All the works on view are dated between 1901 to 1906, during Picasso’s respective Blue and Rose periods. The two palettes dominate the show in Switzerland, as do human figures, when Picasso’s early painting life was focused on portraiture of people on the fringes: harlequins, circus families, and his own lovers in France and Spain.

The exhibitions come at a time when Picasso shows are proliferating worldwide (there were 21 exhibitions in France in 2017 alone). The artist’s son, photographer and filmmaker Claude Picasso, sounded off about this in the press last year, decrying the number of loans going out from the Musée National Picasso-Paris. But even though that institution is one of the lenders to the Fondation Beyeler show, Cluade was complimentary of this one at a press conference in Basel earlier this month.

“In this particular show, we can see Picasso in progress,” said Claude, who is also the son of the art critic and painter Françoise Gilot. “We start with Picasso arriving in Paris, being absolutely stunned and bewildered by this wonderful, incredible life and liveliness in Paris. And then he starts to live in Paris and it’s much more difficult; it becomes much more real. He pays attention to the people around him and they have a difficult life. Even though he frequents the circus, it’s not all amusement.”

Pablo Picasso and his son Claude in 1955. Photo: Bettman.

Some 75 works traveled to Switzerland following the exhibition’s first and larger iteration at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, which featured closer to 300 works. Many well-known pieces from the Blue and Rose periods are on view, including the gloomy painting La Vie, which captures birth, love, and suffering all in one canvas, and dates to the artist’s Blue period. Several of Picasso’s portraits of harlequins, jugglers, and other circus performers feature prominently in the show, which transcend both the melancholic Blue period and the more celebratory and hopeful Rose period.

Also on view is the painting Femme en Chemise, which, according to Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, depicts the artist’s former girlfriend, Madeleine. In 1904, around the time the work was painted, Madeleine found out she was pregnant and, with Picasso’s approval, had an abortion. Little else is known about her, but motherhood and family life was a strong presence in Picasso’s work that followed, including Harlequin’s Family with an Ape from 1905, which is also on view in the show. Richardson surmised that the figures in this painting, and another one from the time, Mother and Child, Acrobats, were also inspired by Madeleine.

Several sculptures also appear in the show. “Whenever Picasso did sculpture, it’s because he’s painted himself into a corner and he couldn’t get out of it, so he had to figure out how to go onto the next step,” Claude Picasso said at the press conference. “And every time this happened, he went and made sculptures, and this allowed him to go to the next step.”

See more images from the exhibition below.

Pablo Picasso, Femme en Chemise (Madeleine) (1904-05). London, Tate, Vermächtnis C. Frank Stoop, 1933 © Succession Picasso / 2018, ProLitteris, Zürich Foto: © Tate, London 2018.

Installation view of “The Young Picasso: Blue and Rose Periods” at the Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2019; © Succession Picasso / 2019, ProLitteris, Zürich. Photo: Mark Niedermann.

Pablo Picasso, Arlequin assis (1901). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Purchase Mr. and Mrs. John L. Loeb, Gift 1960. © Succession Picasso / 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich. Photo: ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Pablo Picasso, La Vie (1903). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Donation Hanna Fund

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zurich 2018. Photo: © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Installation view of “The Young PICASSO: Blue and Rose Periods” at the Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2019; © Succession Picasso / 2019, ProLitteris, Zürich. Photo: Mark Niedermann.

Pablo Picasso, Acrobate et jeune arlequin (1905). Private collection © Succession Picasso / 2018, ProLitteris, Zurich.

Pablo Picasso, Arlequin Assis Sur Fond Rouge (1905). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie, Museum Berggruen © Succession Picasso / 2018 ProLitteris, Zürich 2018. Photo: bpk / Nationalgalerie, SMB, Museum Berggruen / Jens Ziehe.

“Picasso: Blue and Rose Periods” is on view at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland, until May 5, 2019.

Source:www.news.artnet.com