Sheila Hicks aged 84, Textile Artist

Portrait of Sheila Hicks with her installation from “Foray into Chromatic Zones,” London, 2015. Courtesy of PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo.

Over a cup of tea at Sarabeth’s on the Upper East Side,

wanted to talk about her scarf. We met on the occasion of new exhibitions dedicated to the 84-year-old textile artist, but Hicks wasn’t keen on discussing the particulars of her artistic process nor the details of her biography—she’d done so, at great length, for the Archives of American Art. Though she’s esteemed for her innovative, thread-based oeuvre, she dodged questions about it.

“I’m working very hard to make things that are dignified but joyful.”

Installation view of Sheila Hicks, Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands, 2016–17, at The Bass, 2019. Photo by Zachary Balber. Courtesy of The Bass, Miami Beach.

Hicks began her career as a painter—and you can see that in her practice. She translates elements of abstraction, color theory, and painterly gesture into thread, where they perhaps originated. Weavers were making non-representational compositions long before

or

.

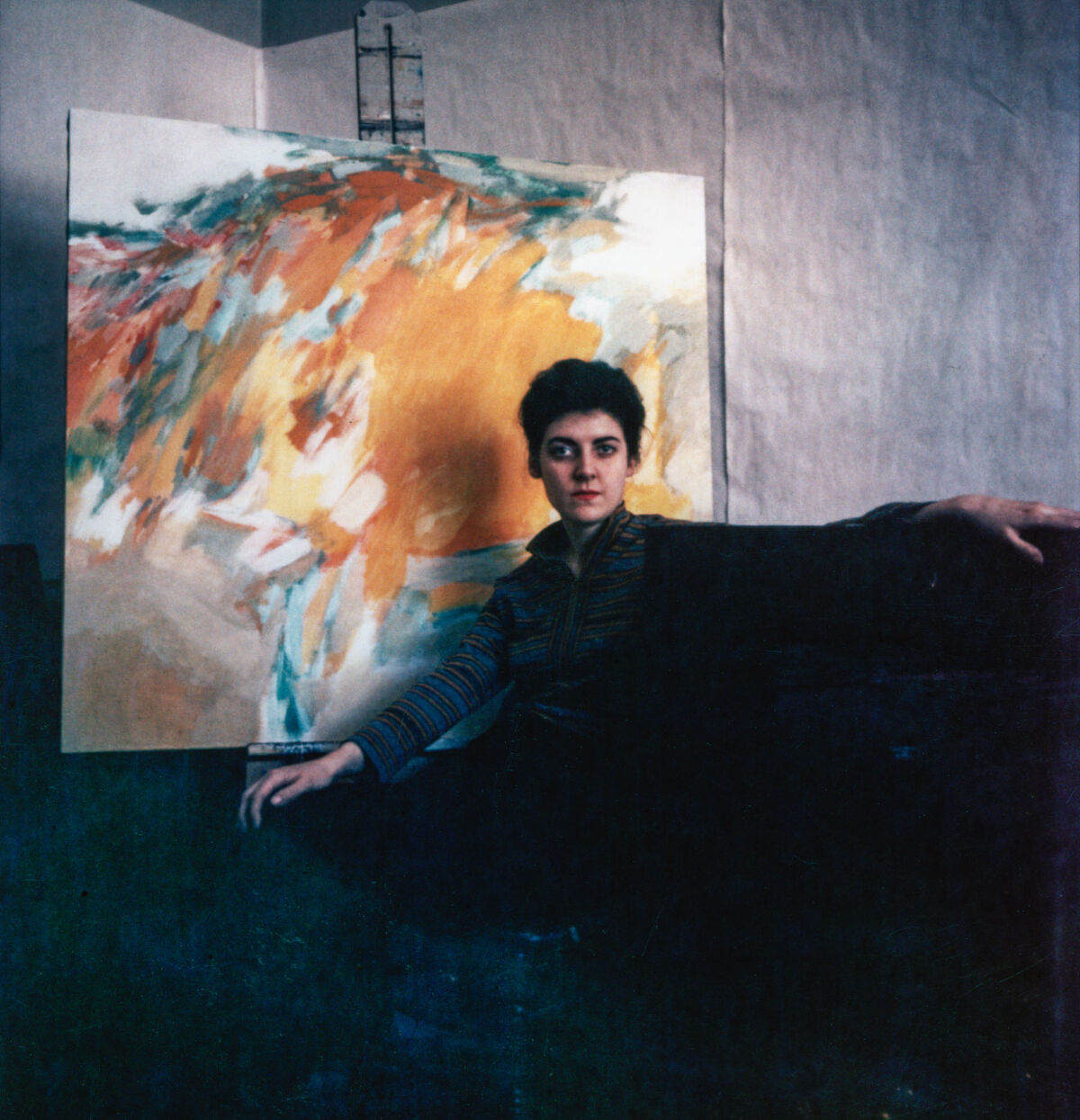

Sheila Hicks with painting at Yale Art School, 1958. Photo by Ernest Boyer.

Hicks’s own experimentations with textiles began while she was studying as an undergraduate at Yale under

in the mid-1950s. The famed instructor and

member taught her about lettering, basic design, structural organization, and color. And when he saw her working with thread, Albers invited Hicks to his home to meet his wife, the prominent artist and textile master

. In Hicks’s version of the story, she enjoyed an epiphany only after she’d left the Albers home and was standing by a bus stop: She realized she could unite Anni’s emphasis on structure with Josef’s principles on color, as she developed her own visual language.

Three other major personalities also inspired Hicks at Yale: art historian George Kubler (an expert on pre-Columbian art); art and architecture historian and critic Vincent Scully; and architect

. “When you go to an art school where the art and architecture and art history departments are all together in the same building, you’re lucky,” Hicks told me. Architecture courses, she noted, help with “raising your consciousness.”

Sheila Hicks, Menhir, 1998–2004. Photo by Zachary Balber. Courtesy of The Bass, Miami Beach.

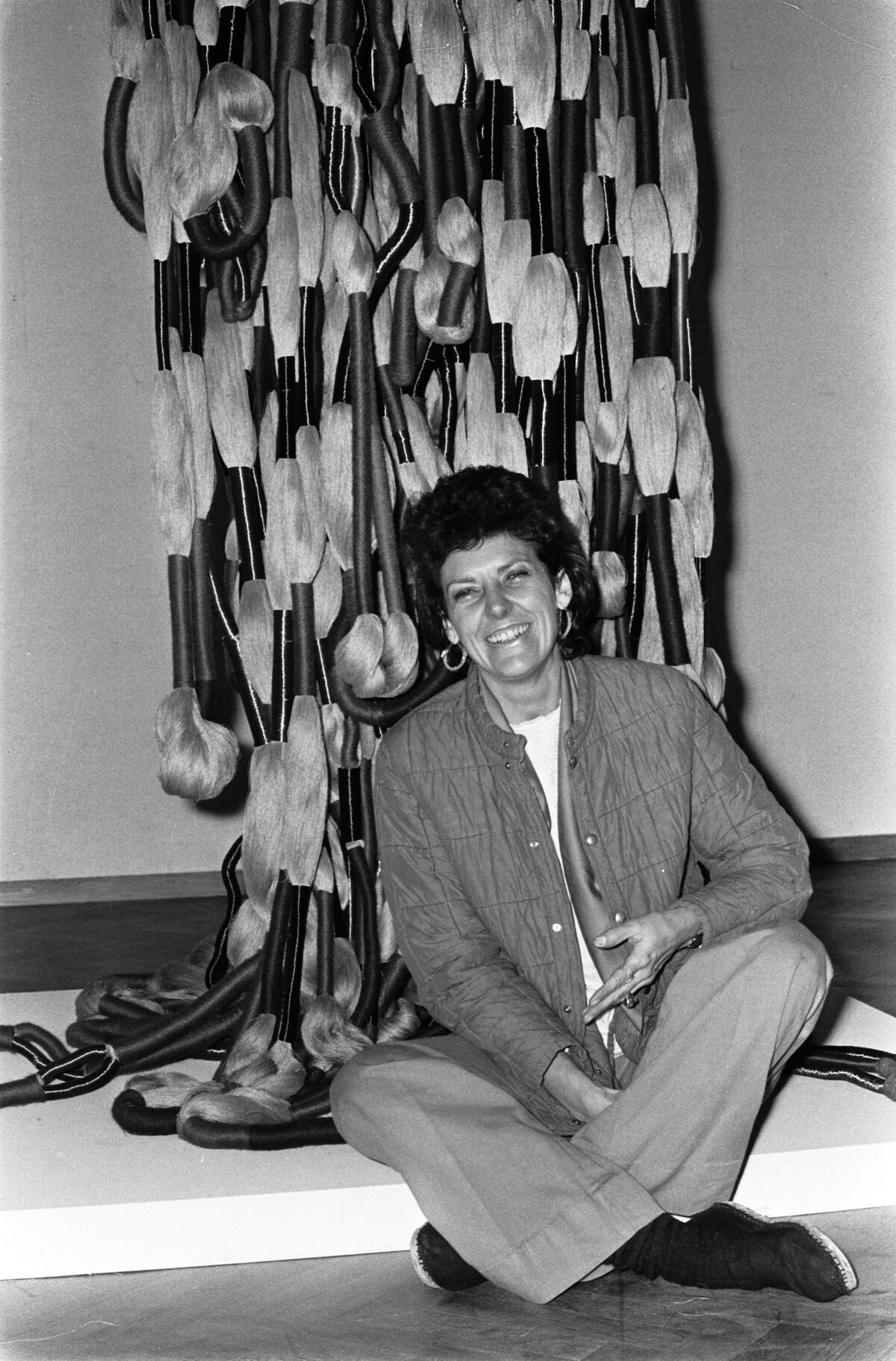

Sheila Hicks organizes an exhibition of tapestries and textile sculptures at the Stedelijk Museum, 1974. Courtesy of the National Archives of the Netherlands.

After finishing her BFA at Yale and before starting the MFA program there, Hicks went to South America on a Fulbright scholarship. After investigating ancient Andean weaving techniques in Chile, she traveled around the continent. She moved to Mexico after finishing her MFA and eventually situated herself among architects: the prominent practitioners

and

. “I like the way architects work,” she told me. “They share, brainstorm together.” She now runs her Paris studio in a similar way, she added.

Sheila Hicks learning to knot with Rufino Reyes, Mitla, Oaxaca, Mexico, 1961. Photo by Faith Stern.

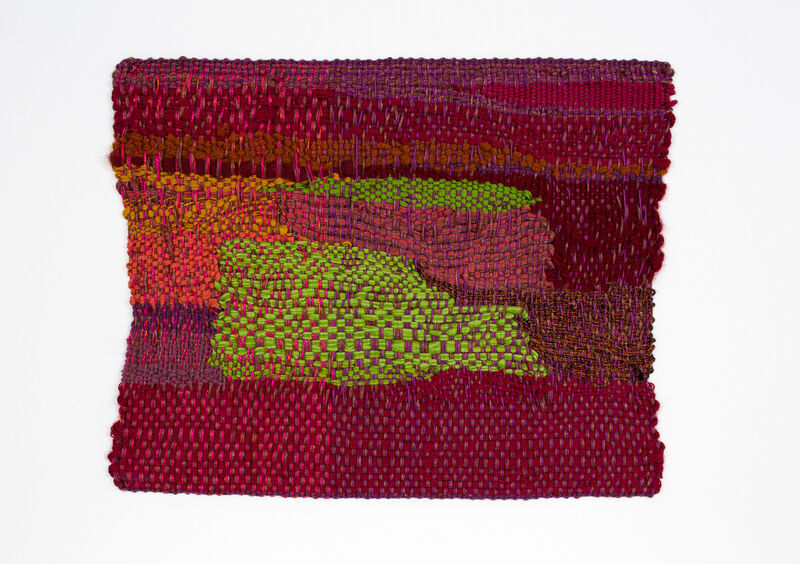

Swatches of Inca designed by Sheila Hicks for Knoll in 1964. Image courtesy of the Knoll Archive.

Another prominent architectural commission came from the Ford Foundation. Hicks created two wall-sized tapestries of intricately-threaded gold discs. She was thinking of beehives and the Foundation’s similarly buzzing, collective spirit. Hicks also made pieces for the

-designed CBS headquarters, the TWA terminal, and Mexico City’s Camino Real Hotel, designed by architect

.

“The idea of its monumentality is to envelop you. You’re not thinking about the grains of the sugar—you’re in a huge lemon meringue pie.”

Sheila Hicks, My Two Friends, 2010. Photo by Daniel Kukla. Courtesy of Demisch Danant.

Sheila Hicks, Torsade II, 2011. Photo by Daniel Kukla. Courtesy of Demisch Danant.

Installation view of “Sheila Hicks: Campo Abierto (Open Field),” at The Bass, 2019. Photo by Zachary Balber. Courtesy of The Bass, Miami Beach.

Hicks thrives in the competitive contemporary art world, even as she promotes cultural elements that can feel conservative.

Installation view of Sheila Hicks, Blue Gros Point, ca. 1990, and Questioning Column, 2016, at The Bass, 2019. Photo by Zachary Balber. Courtesy of The Bass, Miami Beach.

Installation view of “Sheila Hicks: Campo Abierto (Open Field),” at The Bass, 2019. Photo by Zachary Balber. Courtesy of The Bass, Miami Beach.

Installation view of Sheila Hicks, Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands, 2016–17, at Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy, 2017. Photo by Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia.

Portrait of Sheila Hicks in front of Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands (2016-2017), “Campo Abierto (Open Field)” at The Bass Museum of Art, 2019. Photo by Mudita.